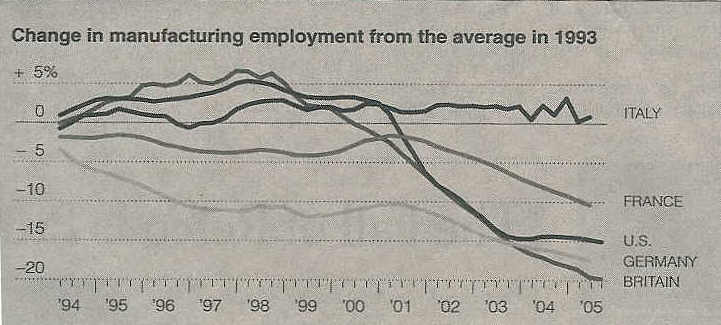

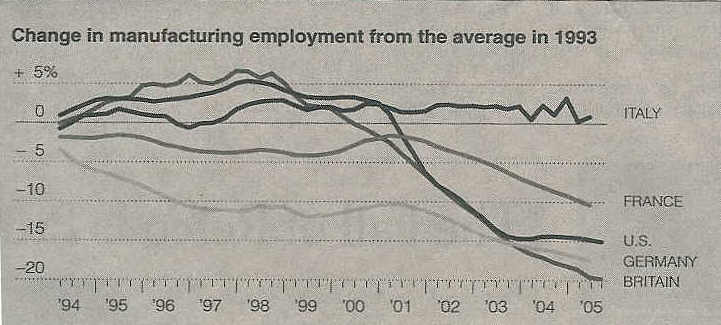

Source: The New York Times, Page B3, October 15, 2005

Source: The New York Times, Page B3, October 15, 2005

Global capitalism is an ailing system. The main question is whether the illness is curable or terminal.

Dollars Without Borders by Michael Hirsh, a book review in the Sunday New York Times, March 5, 2006, Pg. 13 of the New York Times Book Review

Looking at the current state of the world it appears that there are problems with the standard capitalist market economy. It used to be that if you wrote a sentence like the one above people would accuse you of being a communist. Fewer and fewer people even remember what a communist is, so hopefully I'm safe. The observation that capitalism may be in trouble is not made from a Marxist stand point. The observation is based on the fact that automation, computerization and globalization are taking many of the well paying jobs that have been the foundation of the middle class. This is the group of people who are the backbone of the market itself. Without a healthy class of consumers with disposable income, the only market is the wealthy. Even if "high net worth individuals" are gripped by Caligulian excesses of consumption, they cannot buy enough goods to support all of the automated factories or offshore manufacturing. A healthy market needs a healthy middle class, yet this is exactly the class that seems to be shrinking.

What happens if all those displaced white-collar workers can't find greener pastures? Sure, tech specialists, payroll administrators, and Wall Street analysts will land new jobs. But will they be able to make the same money as before? It's possible that lower salaries for skilled work will outweigh the gains in corporate efficiency. "If foreign countries specialize in high-skilled areas where we have an advantage, we could be worse off," says Harvard University economist Robert Z. Lawrence, a prominent free-trade advocate. "I still have faith that globalization will make us better off, but it's no more than faith." [emphasis added]

The New Global Job Shift, By Pete Engardio, Aaron Bernstein, and Manjeet Kripalani, BusinessWeek online, February 3, 2003

From the start of the industrial revolution there has been a constant decrease in the cost of manufacturing. The efficiency of manufacturing, or business in general, is sometimes referred to as productivity. In the early years of the twenty-first century, productivity has been rising in the United States.

Economists have usually viewed rises in productivity as a good thing. Productivity increases have historically allowed wages to rise. In the last few decades, the rise in productivity produced by the combination of automation and globalization has increasingly benefited the wealthy (e.g., those who can take advantage of increasing corporate profits). Overall wages have been stagnating. In some cases wages are being driven downward.

While manufactured goods, like home entertainment electronics and cellular telephones have become cheaper, the cost of housing, food, medical care and eduction has been constant or has risen. The result of rising productivity and stagnate or falling wages is a contradiction. A market for manufactured goods exists only if people have money to spend. As human labor is replaced by computers or robots or jobs are moved to low wage countries people have less disposable income. Yet disposable income is what drives the markets for the fruits of increased manufacturing productivity.

Capitalism has produced a steady rise in income throughout the world. Although the agricultural, industrial and computer revolutions have produced huge dislocations in labor, these painful "reallocations" of resources have worked out for the greater good (or so it is generally argued). It has been a statement of faith that as the power of capitalist economic evolution worked out for the best in the past, so it will be in the future. Such statements of faith, without the support of evidence and analysis, may not necessarily be true. We need to start replacing statements of faith with statistics and analysis.

Commentary: Waking Up From The American Dream Dead-end jobs and the high cost of college could be choking off upward mobility by By Aaron Bernstein, Business Week Online, December 1, 2003

The Death of Horatio Alger by Paul Krugman, The Nation, December 18, 2003

This is a commentary by the economist, professor and New York Times columnist Paul Krugman on the Business Week article listed above.

A Recovery for Profits, but Not for Workers By Louis Uchitelle, December 21, 2003, New York Times

An untested theory is simply a hypothesis and science seeks to expand our knowledge of things by a process of testing hypothesis. In contrast, much of traditional economics theory can be called, appropriately, "ecclesiastical theory"; it is accepted (or rejected) on the basis of authority, tradition or opinion about assumptions, rather than on the basis of having survived a rigorous falsification process.

Why Stock Markets Crash by Dider Sornette, Princeton Univ. Press, 2003, pg. 84.

For most of human history power came from humans, animals, wind or water. The steam engine provided a new source of power for the first time in human history. It ushered in the industrial revolution, modern warfare and the destruction of the old order of kings.

The industrial revolution produced huge dislocations of labor, as people moved from farms to cities, staffing the factories and the offices of the emerging modern world. The terrible working conditions in factories and the rapacious behavior of industrialists like Rockefeller and Carnegie also gave rise to the political theories of Socialism, Communism and Capitalism itself. The process of social transformation brought about by the steam engine, turbines and the internal combustion engine was painful but eventually produced higher income and longer life expectancy. The dead hand of capitalism might have blood stains, but in the end it was for the best (at least for those who survived to live in better times).

The availability of cheap microprocessor based computer power has produced another revolution, sometimes referred to as the "knowledge revolution". Automobile factories in Asia and the United States use robots to perform many of the assembly tasks that were previously performed by human factory workers. Powerful desktop and laptop computer have largely done away with the corporate typing pool. Corporate software and database systems have replaced armies of accounting personnel.

When automation started to halve and then halve again the number of people employed by the large auto factories in the United States people talked about retraining for these displaced workers. In this "best of all possible worlds" scenario these displaced workers would become knowledge workers. Instead of working in dangerous factories full of carcinogens and toxins like auto paint and oil they would work in gleaming office buildings. In this "best of all possible worlds" view, it that all works out for the best in the end. The displaced factory workers go on to "knowledge worker" jobs that pay at least as well and have better working conditions.

The problem with this discussion is that much of it is based on faith that things all work out for the better in the long run. Do we know whether this really happened? For example, what was the inflation adjusted income tax base for Michigan from 1975 to 1995? What about the tax rolls in Pennsylvania over the same period as the steel industry in the US started to move offshore?

Where does increased productivity come from? Many places, but one of the main places is from the automation that IT departments provide. We have been putting other folks out of jobs at a furious rate. We don't have typing pools or mailrooms or nearly as many administrative assistants and customer reps because of email, web sites, and other stuff that comes out of IT.

We rationalize it by saying those jobs sucked anyway...and it's probably true...but many people were depending on those sucky jobs to pay their bills and feed their families. If it's wrong for your boss to save money by exporting your job to India, then it's wrong for your boss to save money by replacing someone else's job with code that you wrote or an application that you administer. If you believe that the people that you helped to displace eventually found other, better jobs, then you have to believe that that is what you will have to do when the time comes.

I don't like this, I don't like saying it, and I don't like management, but it's totally hypocritical to expect mercy after we have acted as executioners for so many years.

From slashdot poster cthlptlk, posting on one of the many slashdot discussions on outsourcing.

The reason that we have statements of faith rather than statistics and analysis when it comes to the waves of change we see around us is that static economic theory is being applied to rapidly changing circumstances. Computer driven automation is without precedent in human history.

Computers and computer driven automation have appeared in every work place, from automobile factories to offices. In the past automobiles were assembled by large labor forces. The "genius" of the assembly line is that a worker only needs to learn a single task, which is performed again and again throughout the day. As a result, assembly line workers can be relatively unskilled. During World War II and for twenty years afterward, factory labor was an engine of prosperity in the United States. Companies like Ford and General Motors where industrial titans, employing large work forces and paying relative high wages, with benefits like health care and retirement plans.

Few unskilled jobs remain in automobile factories. The automobile industry world wide has spent billions of dollars installing automated systems that allow cars to be produced by fewer workers. Automobile assembly lines are composed of robotic and highly efficient human operated systems. Some newly built steel mills now employ only a few tens of people rather than the hundreds that staffed them in the past.

The massive changes produced by automation have not been limited to the factory floor. Before the 1960s, when computer automation started spread into business, office work employed large numbers of people. Financial transactions where labor intensive, recorded by hand on paper, with no more than a mechanical adding machine. Even a medium sized company required a sizable number of workers to manage the company accounts. The financial transactions of a large corporation like General Motors or US Steel required a small army of office workers.

These armies of workers have been replaced by corporate computer systems which support the databases and applications which now manage all aspects of a company's finances. Networks of inexpensive high performance desk top computers, with high resolution monitors and laser printers, have largely replaced secretaries. People prepare their own documents, rather than writing them out by hand or dictating them for typing by a corporate typing pool.

The office and factory jobs that fueled the middle class in the United States and Europe are disappearing. The 1980s, 1990s and the beginning of the twenty-first century have been a time of constant corporate "restructuring", when millions of workers lost their jobs. In many cases only those who are talented and/or well educated can earn salaries that pay for much more than the basic necessities of life. While "knowledge worker" jobs may pay relatively well, increasingly they have no job security.

Retraining won't suffice as technology advances: Computer Revolution May Be Devastating By Robert J. Shiller, Mercury News, March 21, 2004

Source: The New York Times, Page B3, October 15, 2005

Source: The New York Times, Page B3, October 15, 2005

One of the first multinational corporations was probably the banking empire of the Rothschild family, which spanned Europe. Before the twentieth century multinational companies were rare. For example, General Motors was an American company, even though it had manufacturing plants in Europe. Even companies that derived their wealth from holdings outside of their home countries, like Standard Oil, Royal Dutch Shell and British Petroleum were each strongly associated with their home countries.

As corporate markets spread throughout the world, large multinational companies developed. These companies have markets in a number of countries and these foreign markets have, in some cases, became larger than their home country market. Globalization has allowed manufacturing to spread throughout the world as well, continually moving to countries which have lower labor costs.

The factors that have allowed multinational corporations to move into new markets and smoothly relocate production are relatively new. These include:

Globalization has been a long time coming. It required rapid ocean born shipping, truck transportation (in the case of the United States, Mexico and Canada) and air freight.

Taxes also had to be low enough to allow multinational corporations to take advantage of low labor costs. These taxes can come in a number of forms: tariffs at the border, government fees, corporate taxes and corruption (e.g., bribes that the multinational would be required to pay to build factories, import or export material).

Modern China is sometimes called the "Dragon of Asia", in reference to its rising economic power. But thirty years ago China was a very different country. China was a communist dictatorship which was largely cut off from the world community. Private ownership and wealth was illegal in China. China viewed multinational corporations as tools of colonialist foreign powers. China had nothing resembling commercial law (e.g., bankruptcy, copyright and contract law).

In the 1950s China fought a land war in Korea against the United States (several hundred thousand Chinese soldiers died in this war). In the 1960s and 1970s China backed North Vietnam in the war it fought against South Vietnam and the United States. The Cultural Revolution in China caused famine and political chaos. The Chinese currency was not traded in the international foreign exchange market. Few Chinese students were allowed to attend Universities in the US or Europe.

In almost every respect China is a different country today. While there is occasional saber rattling between the United States and China, relations between the two trading partners are relatively cordial. Succession in the Chinese "Communist Party" is orderly. The Chinese currency (the yuan) trades on the international foreign exchange market. China has laid the foundation for commercial law. Instead of being a criminal offense, wealth is officially desirable (It is good to be rich said Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping). China sends many of its best students abroad to study. As a global trading powerhouse China is no longer isolated. It has massive infrastructure in its ports and airports to support the export of goods manufactured in China. Corruption is still a problem, but it seems to be less of a barrier to doing business than it was in the past.

For much of its modern history, India was governed by the so-called License Raj, a socialist-inspired system that required government permits for almost every aspect of business. The raj was an impediment to growth and a reason India has lagged behind China, which began its economic reforms in the 1970s. In India, companies could produce only the amount allocated to them by the government under the terms of a "license." In order to expand or start a new product line, businesses also needed state approval. The government regulated everything from exports to foreign-exchange transactions.

India's Economy Gets a New Jolt From Mr. Shourie by Jay Solomon and Joanna Slater, The Wall Street Journal, Pg. A1, January 9, 2004

India is another example of a country where change has supported globalization. India was a colony of Great Britain and the reaction against its history of British colonial domination echoed throughout Indian politics for decades. Like China, India was extremely suspicious of European and US multinational corporations. India was a socialist country with high tax rates and strict controls on capital flows, both into and out of India. There were also high tariffs on imported goods. This combined with a glacial customs made import of machinery, computers or telecommunications equipment into India difficult. Corruption added another hidden tax, as each level of bureaucracy required a bribe to move permits forward.

Economic liberalization in India began in 1991. The liberalization of the India tax system, the reduction of tariffs and the relaxation of controls on capital flows has allowed India to take part in globalization, particularly in services and information technology (i.e., software development).

Mexico, Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand have all undergone similar changes to some degree in order to support globalization. The end result has allowed manufacturing to move from higher cost countries to lower cost countries. For example, in the past the United States, especially in the Southern States, has been a manufacturer of textiles. Now textile production has moved almost entirely from the United States to low cost countries. This has also happened with computer memory chips and electronic board assembly.

In the 1980s and '90s, two-thirds of workers who lost jobs in manufacturing industries hit by overseas competition earned less on their next job, according to a study by Lori Kletzer, an economist at the University of California Santa Cruz. A quarter of workers who lost their jobs and were re-employed saw income fall 30% or more.

Behind Oursourcing Debate: Surpringly Few Hard Numbers by Jon E. Hilsenrath, The Wall Stree Journal, Pg. A1, April 12, 2004

The book Rivethead: Tales From the Assembly Line by Ben Hamper is an account of two automobile factory workers in the 1970s. The work on the assembly line was mind numbingly boring. Rivithead was the true story of two relatively unskilled "shoprats" who got drunk every day in the parking lot at lunch. The quality problems that resulted from a workforce where this behavior was not unusual was one of the reasons that Japanese cars and trucks made inroads in the United States.

Low skill assembly line jobs are largely gone in the automobile industry. They have been replaced by automation or labor in low cost countries. Many of the suppliers to General Motors and the other large automobile companies have moved assembly work to lower cost countries like Mexico, where there are no union contracts and environmental protection laws are limited, at best.

Globalization is now moving up the "food chain". Skilled manufacturing jobs are moving offshore as well. These jobs include welders, tool and die makers and skilled machinists. The National Tooling and Machining Association estimates that 30% of the tool makers have shut down from 2000 to 2003.

These workers are the manufacturing and crafts equivalent of knowledge workers. They work in skilled manufacturing jobs that require years to master. Many of the people who do these jobs take pride in their work. These are jobs that have paid well. When these jobs disappear, they are rarely replaced by jobs with equal or better pay.

Die Is Cast: With Foreign Rivals Making the Cut, Took Makers Dwindle by Timothy Aeppel, the Wall Street Journal, November 21, 2003

Laid-Off Factory Workers Find Jobs are Drying Up for Good by Clare Ansberry, The Wall Street Journal, July 21, 2003, Pg. A1

In the 1990s, while hundreds of thousands of manufacturing jobs were moving offshore or being replaced by automation many writers claimed that the future belonged to the knowledge worker: software engineers, electrical engineers and financial analysts. Some suggested that workers displaced from manufacturing could be retrained to meet the huge demand that was expected for knowledge workers.

There were a few problems with the idea that everyone could become a knowledge worker. Many of the skilled craftspeople who lost their jobs to globalization where people who made their career choice because that is where their skills lay. These were the people who failed math but got A's in metal shop and drafting. While they might not have had a gift for mathematics or english, they are mechanically gifted people who like working with their hands to build things. There is no direct path to "knowledge work" for these people.

Another problem with the idea that the future, at least in the United States, belongs to the knowledge worker is that it turned out to be wrong. Those high paying knowledge worker jobs are now being globalized as well. Jobs in software development, electrical engineering, tax preparation, financial analysis and legal research are all being moved from the United States to lower cost countries.

Legal Research And Back-Office Work to Go Offshore Next, Information Week, December 9, 2003

What goes around comes around. Remember all of those insane signing bonuses and perks that useless rockstar programmers and IT staff were getting 2-3 years ago during the boom? Well, now we get to see management and HR getting their chance to get some of their own back.

It's best to look at this as an exercise in schadenfreude: all of those wanna-be technolibertarians who spent most of the 90s shuddering and twitching at the mere mention of unions, collective bargaining or any other manifestation of labor rights now get to find out the hard way what life is like when management holds all of the cards.

That cold, unwelcome sensation invading your rectum? That's the invisible hand you professed to adore so much last year. Enjoy!

Doktor Memory, a poster in a slashdot.org discussion

The movement of Information Technology (IT) jobs offshore has been going on for a number of years. The first jobs to move were telephone customer support. Routine software maintenance jobs for older software applications were next. As has been the case with manufacturing jobs, where first assembly line jobs went first, eventually followed by skilled jobs like tool and die making, the computer industry jobs that have moved overseas have moved "up the food chain".

One of the first steps up "the food chain" involved custom applications development for internal use by large corporations. In the past these applications have been developed by corporate Information Technology (IT) departments. In increasing numbers, corporations have moved their IT development groups offshore and fired most of their US engineers.

In many cases the custom applications developed by corporations and banks were relatively simple. Complex software design and development remained in the United States. Since the technology downturn in 2000 this has started to change. While corporations have been firing workers in the United States, the same corporations have been investing in India.

A "Made in India" tabbed Intel chip is likely to be released by the year 2005-.06. This was announced by Intel India, President, Ketan Sampat. "We are in a three year development phase. So a "Made in India" chip is likely to be released in the year 2005-'06."

He went on to add that the design center in India is developing a high-end 32-bit computing Xeon chip processor, which has apparently not been code named yet. But the release would likely be the first fully designed chip from the Intel stable in India.

Intel plans "Made in India" chip by 2005", Cyber India On-Line (CIOL)

With few exceptions every large technology company in the United States now has design and development centers in India. This includes IBM, Intel, Oracle, Sun Microsystems, Microsoft, Adaptec, Cadence and Synopsys. These offshore engineering groups are not just designing and implementing simple software or hardware components. They are involved in sophisticated product development.

In late 2003 and early 2004 companies like Intel and Juniper Networks (a company that makes computer network routers that compete against Cisco) have reported strong profits. While India is experiencing a hiring boom, strong corporate profits have not translated into jobs for unemployed engineers in the United States.

Between 2000 and 2003, employment in the U.S. among computer programmers, as defined by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, fell 182,000 to 563,000.

Behind Oursourcing Debate: Surpringly Few Hard Numbers by Jon E. Hilsenrath, The Wall Stree Journal, Pg. A1, April 12, 2004

In a commercial setting, the development of new software and maintenance and enhancement of existing software can be divided into three categories:

Internal corporate software. This involves the development and maintenance of custom software to support the business. The "customers" for this software are corporate business units. This software is rarely sold to customers outside the corporation. The cost for software development and maintenance is part of the corporate overhead.

Consulting. In consulting, software engineers are paid to develop or maintain software for a client. Consulting is usually done on either a fixed price or "time and materials" (e.g., hourly rate) basis. In most cases the consulting company charges the customer a fee and then pays the consulting engineer some fraction of that fee. Consultants may be paid to develop internal corporate software or to support corporate research and development.

Research and development (R&D). This involves the design and development of new products which are intended for resale to multiple customers.

The cost of corporate software development is part of the overall corporate overhead. By cutting this overhead companies can raise their profit margin. As a result, corporate software development (usually performed by corporate information technology departments) has been an area where outsourcing to low wage countries has had a big impact. Corporate applications also tend to be relatively uncomplicated, which has made outsourcing easier. A number of articles have appeared in the press on companies that have moved most of their IT departments overseas (usually to India or China).

Companies that provide software consulting services are selling a product: the labor of their software engineers. The customers who purchase these services would like to get them at the lowest cost possible. Indian companies like Tata have been able to offer software consulting services at about 25% of the cost charged by US consulting companies.

The history of software development is full of accounts of software development projects which were either not completed or did not deliver a quality product. Most people who purchase software consulting services are aware of these "horror stories" so they do not make their decisions solely on price. However, if there are two equally qualified consulting companies they will chose the cheaper alternative.

Research and development (R&D) costs are incurred during the design and development of a product. In the case of software or computer hardware development, engineering salaries are a significant fraction of these R&D costs. After the product is developed, sales and marketing become dominate. Most technology companies that are beyond the start-up phase spend less than 20% of their revenue on R&D. Sales, marketing, corporate overhead, product maintenance and enhancement, and manufacturing make up the other 80%. R&D costs are not a recurring cost. For a given product (or product version) R&D costs come to an end when the product is released.

The savings that can be realized by moving R&D from the United States to a low wage country is limited by the overall amount that the corporation spends on R&D. Since R&D expenditure is not the major cost incurred in selling a new product, the savings that can be realized by the corporation are proportionally fractional.

Of the three categories in software development (or engineering in general), R&D represents the technology future of the United States. This is the path by which new products are developed. R&D represents the risk capital that corporations put into their future and it usually attracts some of the best engineering talent.

Unlike corporate software development or consulting, savings on R&D expenditures are unlikely to effect the overall corporate profit and loss statement. Yet these fractional savings are being used to justify hollowing out the technology infrastructure of the United States. Every major technology company in the United States has opened R&D development centers in low wage countries.

Poisoning the roots of the techno-boom by Jeff Taylor, January 14, 2004, Salon

Moreover, it is found out that the Americans are shying away from the challenges of math and science. A recent National Science Foundation Study reveals a 5 per cent decline in the overall doctoral candidates in the US over the last five years.

The India side story: India produces 3.1 million college graduates a year, which is expected to be doubled by 2010. The number of engineering colleges is slated to grow 50 per cent, to nearly 1,600, over the next four years.

Finally, Bangalore beats Silicon Valley by Satya Prakash Singh, India Times, January 06, 2004

The Chief Executive Officers of technology companies have been complaining for years about the poor quality of eduction in the United States and the decline in the number of students studying mathematics and science. The implication is that "something ought to be done", presumably by the government to fix this sorry state of affairs. The most frequent "something" mentioned by the multi-millionaire CEOs is an increase in government research spending. While they await improvements in the educational level of US citizens, these companies have pressed for ever larger numbers of visas for engineers from outside the United States (primarily from India). These constant demands for foreign engineers have only been moderated by the political realities of record engineering unemployment at the beginning of the twenty-first century.

There are a number of reasons for the decline in math and science education in the United States. Some of these involve the society at large. For example, the rise of the media culture in opposition to a culture of books. Some of these involve the government. For example, a decline in funding for undergraduate education. There are also factors that directly involve these captains of technology companies who bemoan what they see as the decline of their country: opportunities and job security for workers in the United States.

As undergraduate student aid has declined, the cost of a college eduction has risen. A college education has become more and more difficult to afford for anyone who is not fortunate enough to be born into a wealthy family. Many students fund their college education with student loans. Even students attending state colleges can graduate with a heavy burden of debut. This debt and the time and effort that these students have put into their eduction represents an investment in their future.

As companies like Intel, H-P, IBM, Oracle and Cadence move jobs to low cost countries, opportunities in the United States are declining. There are probably only a million or so engineering and computer science jobs in the United States (the Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that there are about 500,000 programming jobs in the US). Moving 100,000 engineering jobs offshore may have a huge impact on the US job market for engineers. Why should a prospective engineering student invest tens of thousands of dollars in their future if all they can expect is job insecurity, declining pay and age discrimination?

In contrast, the "information technology" sector if India is booming. An Indian student has every incentive to study engineering, because it promises a better life.

The end result is that the technology infrastructure in the United States is being hollowed out as sophisticated "knowledge worker" jobs are moved overseas. As these jobs disappear in the United States, there will but fewer students studying science and engineering. These students are the "seed corn" for the crop of future technology in the United States. Without a strong base of technology workers, the United States will lose its technology leadership.

A decline in technology leadership in the United States does not necessarily mean that a decline in the profits of multinational corporations will follow. Although these corporations were given birth by the technology base and capital markets of the United States, they have less and less allegiance to their country of origin. What is lost in the United States is gained by India or China. Although opportunity may decline in the United States, the jobs exported overseas will create new markets for these corporations. Lower labor costs translate directly into higher profits and fatter bonuses for corporate executives, especially the CEO.

Corporate executives are happy to talk about what the government of the United States can do for them. With perhaps less candor they will talk about their obligations to their shareholders. Corporate executives talk constantly about how they must take what ever measures are necessary to assure that they can compete in the global market. This last point is usually made to justify the movement of high paying jobs overseas.

I have yet to read about any corporate executive outside of the defense industry talking about what they owe their country. The United States government is expected to provide tax breaks, export loans, business insurance and a "corporate friendly" environment. These CEOs don't seem to feel that they owe their countries of origin anything in return. If corporate profit margins are improved by hollowing out the technology base of the United States, damaging our national future, this is not the problem of the technology executives.

The dominance of the US military is based, in part, on the fact that modern weapon systems use the most advanced technology in the world. The US technology base makes these weapon systems possible. If the US technology base is hollowed, US military power will suffer.

In other contexts actions by US citizens which harm the long term military power of the United States would be considered something close to treason. Apparently such standards and responsibilities don't apply to those who lead multinational corporations.

The Indian companies and Indian employees win, and so do the American companies that outsource. For the American companies, this clearly is an instrument for them to improve their productivity, reduce their cost and have higher quality. And that is required for their financial longevity and the robustness of their business models.

And for the Indian companies, it creates not only growth but also a tremendous amount of jobs, which are required in a country like India and is helping spur its overall economic growth. So I think it is a healthy development; it is part of globalization. For the last several years, we have all been talking about lowering the barriers of protectionism between countries, and this is part of that process.

Nadan Nilekani, CEO, Infosys Technologies. "Nilekani is spearheading the burgeoning movement to shift IT work offshore that has corporate leaders seeing green and U.S. tech worker advocates seeing red"

From an interview with Nadan Niledani, On the outsourcing hot seat, by Ed Frauenheim, January 20, 2004, News.com

This essay is entirely focused on workers in the United States. If a broader, more global view is taken, especially if this view extends over more than one lifetime, globalization may be seen as a force for the greater good of humanity. Jobs that are lost in the United States create opportunity in developing countries like India, China, the Philippines and Thailand. Perhaps over a few lifetimes globalization will increase the living standard worldwide.

On the basis of population the United States uses a disproportionate fraction of the worlds resources. This includes natural resources, like oil, but also includes less tangible resources. For example, a significant part of the US trade and budget deficits are financed by investors and governments outside the United States.

Perhaps globalization is a way of leveling out income and resource use throughout the world. If this is the case, the United States is in for a big shock as the US standard of living starts to be averaged with the standard of living of more populous developing countries like India and China (which together have about seven times the population of the United States). While there may be people in the United States who are noble enough to sacrifice their standard of living for the benefit of workers in developing countries, this is not a choice most people in the US are willing to make.

Those who support globalization either claim that it is for the greater good of the United States or that it is an irresistible force (we might as well accept it, since we can't stop it). Globalization would find few supporters in the US if people believed that US jobs are being sacrificed so that engineers in Bangalore India can have a better life. Or that globalization would reduce the standard of living in the US to the level of Bangalore.

When Webodrome places a 10-centimeter ad in the Times of India, advertising for programmers, the company will receive about 300 or 400 responses, 200 of which will be recent college graduates, Doshi says. Technical colleges send their students as unpaid interns to Webodrome to get trained for credit.

The surplus of recent college grads looking to get their foot in the door is often exploited by unscrupulous companies. Some small firms pay only 1,000 or 2,000 rupees a month, even after a six-month tryout. Other firms require a deposit of tens of thousands of rupees before they will hire you, which is repayable according to a contract, only after two years of service, says Dwpa. You cannot leave the company during that contract period, or you forfeit the deposit.

And some just demand really long hours -- 12 hours a day, not including the commute: "There are many companies that are doing this," says Dwpa."That's the level of exploitation. If you're going home at 9 p.m. at night, they still expect you to come in sharp on time. Whether you reach your house at 12 at night, they do not care."

No sweatshop here By Katharine Mieszkowski, Salon, April 12, 2004

There is a constant stream of articles in the US press about yet another multinational company opening an engineering center in India where they will employ hundreds or thousands of engineers. Where are all of these engineers coming from? India is a country where many cities do not have reliable electric power. The roads in much of the country are poor. Only recently has starvation become a thing of the past in India. How is it that India can educate all of these engineers?

A high quality University eduction is expensive. Historically, this kind of education has only been available in the "first world", which is why developing countries send their promising young men and women to school in the US and Europe. The Indian government founded the Indian Institutes of Technology to provide access to high quality education in India. This objective seems to have been met and IIT apparently provides excellent education to a very talented student body (admission to IIT is based on exams and is very difficult).

However, IIT graduates only a few thousand students a year. Some IIT students go on to post graduate work and jobs abroad in the US or Europe. The IIT graduates who remain in India constitute the core of India's technology industry. But IIT cannot compete with the vastly larger University system in the US or Europe. If IIT were the only source for Indian engineers who are filling the jobs moved from the United States, offshoring to India would quickly have come to an end. (in fact, as this article notes, increasingly there is a shortage of well trained Indian engineers).

In training computer science students, University programs attempt to provide a broad background. While most Universities have classes in Java and C++, they rarely offer classes in narrow industry related topics like writing software for the Oracle database or Microsoft .NET software development. Instead a University computer science education includes mathematics (calculus, discrete mathematics) and concentrates on computer science principles, rather than specific applications. Those who design these programs would like to believe that their students can work in a broad range of areas throughout their careers.

One possible answer to the question "Who is training the Indian IT Workers?" is that a University education is not needed for many programming jobs. Those who run Universities argue that the eduction their institution provides prepares you for an intellectual life. Many of the courses that computer science students take are not directly applicable to their future jobs. This style of eduction is a luxury of the "first world". A developing nation, like India may take a more direct path in educating students for the jobs that are moved to India.

An education that focuses on training future IT workers to staff the offshoring industry would concentrate on courses that are useful for getting a job. The english language would be studied, but english literature, history, philosophy, art, biology, chemistry and physics would not be part of the curriculum. While basic algebra might be useful, calculus and discrete mathematics is not necessary, since few IT jobs require a knowledge of mathematics.

Rather than studying general computer science principles, specific technology would be studied. For example, instead of database principles and design, Oracle, Sybase and Microsoft's SQL-server would be studied. Java and the Java Enterprise environment would be covered. An in-depth understanding of data structures and algorithms would not necessarily be needed, since Java has an extensive class library. Students would study Microsoft's technologies, like Visual Basic, the C# language and the .NET environment.

While I know very little about the Indian educational system, I speculate that many of the jobs that are moved offshore are being staffed by people who are graduates of the sort of trade school eduction I have described above. For many of the entry and mid-level programming jobs that are being moved offshore from the United States, this eduction is probably sufficient, at least in the short run.

By accident I encountered one of these Indian "IT trade schools". I got a note from someone at an NIIT email address. The email was written in very poor english and related to one of my web pages. I took a look at the NIIT web site and found the following descrition of their "heritage":

NIIT, the brainchild of two, young Indian entrepreneurs, pioneered and nurtured the concept of high quality IT education in India. Set up in 1981, NIIT has trained one out of every three software professionals in the country and become a beacon in the global IT revolution. From introducing computers to the people of India, to providing advanced IT skills to students and professionals, NIIT has evolved into a training powerhouse. While our special-priced, IT programs have enabled ordinary citizens to achieve computer and Internet literacy, our career education has shaped the lives of millions of individuals.

This is a commercial for profit trade school. Whether their claims to have trained "one out of every three Indian software professionals" is overstated or not, I can't say. I do think that it is safe to say that the training provided by NIIT differs dramatically from the training someone gets at the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT). Unlike IIT, the for profit NIIT seems to be turning out "software professionals" with very little knowledge of computer science.

There is a toxic style of management behavior that is seen in both corporate management and in investment fund management. This involves managers who get rewarded for short term gains, while avoiding the long term consequences of the decisions that delivered those short term gains. For example, a manager might get a yearly bonus for delivering savings in the corporation Information Technology (IT) department by offshoring software development and maintenance. If the cheap labor hired in India turns is not as skilled as the US engineers they replaced, the effects may not be appear for a year or more. By that time the manager may have moved on to another job.

A number of offshoring projects have the feel of short term gain at the cost of long term loss. The infrastructure in India, whether it is clean water, reliable electricity or quality education falls far behind Europe and the United States. While software programmers from Indian IT trade schools may be cheap, it appears that a shortage is starting to materialize in skilled university graduates.

Unlike Silicon Valley, however, the employees in India didn.t value stock options as much as folks do in Silicon valley. It was understandable, however, given they had never seen a friend hit it big or seen the Google like wealth effects which occur every 5 years in the Valley. Hence, they argued more for cash compensation. This combined with the fact that we were going after the best in Bangalore (the most impacted city in India) increased our exposure to wage inflation.

Bangalore wages have just been growing like crazy. To give you an example, there is an employee of ours who took the first 5 years of his career to get from 1% to 10% of his equivalent US counterpart. He then jumped from 10% to 20% of his US counterpart in the next 1 year. During his time with us (less than 2 years) he jumped to 55% of the US wage. In the next few months we would have had to move him to 75% just to keep him at market.

Keep in mind that Riya are at the leading edge of this trend. We tend to only hire folks from IIT or other top schools. We tend to only hire the smartest folks from these schools. We only hire in Bangalore (just too hard to have three offices). We tend to only hire folks with a lot of experience. These are all characteristics that are critical for technology startups, but not necessarily for a big company like IBM or a services company like Infosys who can afford to train new graduates. I do believe that other startups in Bangalore will see the same issue in 12-24 months.

Munjal Shah, CEO of Riya, an Internet software company in Bengalore

Recognizing Deven: Episode 26 - India Grows Up, April 24, 2007

Andrew Leonard's How the World Works blog entry Bangalore offshores to Silicon Valley originally pointed me to Munjal Shah's blog entry.

The job market at the start of the twenty-first looks bleak. While corporate profits are up and our appointed president crows about the economic boom created by his party's massive deficit spending, few jobs are being created to replace the high paying jobs that have moved offshore. In many cases the jobs that are being created pay less than the jobs that were lost.

Some people believe that the current depressed state of the job market is temporary. They point to rising wages for skilled engineers and scientists overseas and to a future labor shortage in the United States. This labor shortage will be created by the fact that the "baby boom" is aging and will soon be retiring. Fewer young people are available to fill the jobs that these aging workers will leave behind when they retire. However, society is committed to support these retirees through programs like Social Security. Seen in this light, the productivity gains realized by automation and globalization are a long term benefit as the profits realized through productivity will go to support the aging population.

Even with automation and globalization, these demographers believe, there will still be a worker shortage. Companies that currently treat their employees poorly or practice age discrimination will be punished for their behavior as their employees leave for better jobs. A shortage of labor will cause salaries to rise and retaining employees will become a priority for management.

For those in this future work force, this sounds like a better world than the one we are currently living in. It would be nice to look back on this essay in a few years and see how wrong it was. And who knows? The future constantly surprises us.

Sadly, there are a number of reasons why this rosy future may not arrive.

A number of writers have observed that jobs that are moved offshore never come back. They are gone forever. If offshoring trends continue some of the jobs that are vacated by retirees will simply move to low wage countries.

The thesis that there will be a wave of retirements is also open to question. Billions of dollars were lost in the US stock market downturn in 2000. Billions more were lost through corporate fraud at companies like Enron, Adelphia, Health South and Worldcom. For those whose retirement savings were reduced to a fraction of their previous value, there will be no retirement. Assuming that jobs for older workers are available, those whose retirement savings were savaged will only stop working as a result of disability or death. For others, retirement savings were used to survive after they lost their jobs in the economic downturn. Many of those who avoided stock market losses, corporate fraud and were lucky to have a job in the early part of the twenty-first century have not able to save enough for retirement. As a result, many people will be forced by economic circumstances to work beyond "retirement age".

What will it take to get back in the fight? Understanding the real interests and deep opinions of the American people is the first thing. And what are those? That a Social Security card is not a private portfolio statement but a membership ticket in a society where we all contribute to a common treasury so that none need face the indignities of poverty in old age without that help. That tax evasion is not a form of conserving investment capital but a brazen abandonment of responsibility to the country. That income inequality is not a sign of freedom-of-opportunity at work, because if it persists and grows, then unless you believe that some people are naturally born to ride and some to wear saddles, it's a sign that opportunity is less than equal. That self-interest is a great motivator for production and progress, but is amoral unless contained within the framework of community. That the rich have the right to buy more cars than anyone else, more homes, vacations, gadgets and gizmos, but they do not have the right to buy more democracy than anyone else. That public services, when privatized, serve only those who can afford them and weaken the sense that we all rise and fall together as "one nation, indivisible." That concentration in the production of goods may sometimes be useful and efficient, but monopoly over the dissemination of ideas is evil. That prosperity requires good wages and benefits for workers. And that our nation can no more survive as half democracy and half oligarchy than it could survive "half slave and half free" - and that keeping it from becoming all oligarchy is steady work - our work.

This is Your Story - The Progressive Story of America. Pass It On. by Bill Moyers

Text of speech to the Take Back America conference sponsored by the Campaign for America's Future

June 4, 2003, Washington, DC

Since the end of World War II the United States has been a society of egalitarian ideals, if not egalitarian reality. Education, talent and hard work are supposed to be the path to well paying jobs and the middle or upper-middle class. At the beginning of the twenty-first century this no longer appears to be as true as it once was. In the last decades the pay for corporate executives has increased astronomically, while factory jobs have disappeared and many skilled workers have declining jobs prospects.

Automation has had a huge impact on ever facet of our lives. Welders in automobile factories have been replaced with robots. The corporate typing pool has disappeared in an era of desk top computers and Microsoft Word. Fewer bank tellers are needed now that automated teller machines (ATMs) are everywhere. Airline tickets can be purchased and printed out via the Internet and the World Wide Web, so fewer ticket agents are needed. This trend is not going to stop. As time goes on more and more jobs will be taken over by computers and automation.

In the past people talked of computers and automation "freeing" people from tedious jobs like those on the assembly line where humans were forced to act like the robots that eventually replaced them. This begs the question: freed for what? The answer given has been: more rewarding, challenging jobs. Jobs that are enjoyable, rather than drudgery. Usually these jobs are the those of skilled workers and knowledge workers. These are exactly the jobs that are now moving to low wage countries.

The corporate executives who move these well paying jobs offshore claim that they have no choice. They say they are struggling to survive in a brutal capitalist jungle. Its ugly out there, they claim, and only the strong survive. Remember, these executives will say, we are competing in a global market. Their competitors are reducing their costs and lowering their prices by offshoring skilled jobs. To compete these executives have no choice but to follow.

A similar argument could be made for removing environmental regulations in the United States. Companies like Dow Chemical or the mining company Phelps Dodge could claim that they cannot be expected to follow environmental regulations to protect the air, water and ground from contamination. These companies compete with companies in Russia, India and China that follow few, if any, environmental laws. These foreign companies can undercut Dow Chemical or Phelps Dodge. Sorry about the poisoned air and water, but this is the price for surviving in a global marketplace.

Most people would not agree agree to drink poisoned water, breath polluted air and live in a blasted moonscape of mine tailing so that a multinational company can compete against foreign companies that don't follow environmental regulations. Instead the discussion has centered on making a "level playing field". Rather than accept a polluted environment in the United States, foreign companies that operate without environmental regulation would have tariffs slapped on their products that are imported into this country.

The equivalent to Rachel Carson's Silent Spring has yet to be written on wages and jobs. Although more attention seems to be paid to the environment, jobs and wages are not without regulation. There is a minimum wage and immigration into the United States is, in theory, controlled. In reality the minimum wage does not provide a living wage and companies like Wal-Mart reduce their labor costs by either directly or indirectly using illegal workers. The idea that minimum wage laws, workplace safety laws, and immigration laws should disappear so that multinationals can compete with low cost foreign labor would be only slightly less popular than the suggestion that we should drink poisoned water for corporate profit.

When the issue of offshore outsourcing comes up, many commentators and corporate executives claim that regulation and taxes are not the solution. You can't fight the "dead hand" of capitalism and any attempt to do so is doomed to failure. Those who are making these arguments are pretending that the United States exists is some kind of unrestricted "free market" environment. This is a willful misreading of reality. There are environmental, labor and wage regulations. There are tariffs that were imposed to preserve the US automobile industry, farm programs that cost tens of billions of dollars, cheap loans from the US import/export bank and a vast array of other corporate "welfare" programs. These corporate "welfare" programs do benefit those who donate money to politicians, but they also have political support because these programs provide jobs.

The continued loss of jobs to automation and computers does not have any obvious solution. In this case the jobs disappear as they are taken over by technology. In contrast, the skilled jobs that are moved offshore still exist and are still done by skilled workers. It is just that these jobs are no longer in the United States. We are not helpless before the trend of offshore outsourcing. The United States is not powerless to stop the hollowing out of our technological infrastructure. We do not have to sacrifice our future for a few percentage points of corporate profit.

Tax law and corporate regulation support the movement of jobs offshore. This can be changed. The United States government can recognize that R&D jobs are a critical part of the future of the United States. Tax deductions for R&D that is done offshore should be removed. The US tax deduction for salaries paid to offshore workers should be removed or modified. The executives who have become fantastically wealthy because of the infrastructure provided by the United States must come to realize that they cannot take advantage of this infrastructure without obligation. Corporations must be profitable so that they can survive and provide jobs. But these profits cannot be maximized at the cost of the future of the United States.

What is ironic is that "free trade" ideology seems to exist only in the United States. Most countries in Asia have policies in place to protect local industries, especially industries that they view as strategic. Yet it is these very same Asian economies that present the largest threat to the economic infrastructure in the United States.

The policy makers in the United States must come to realize that protectionism is not bad policy when it comes to protecting our nation. When protectionism is mentioned some argue that this will lead to "trade war" and economic meltdown. They point to the Great Depression in the 1930s as an example. What the "free traders" fail to mention is that if India stopped purchasing US services and goods, there would be no effect on the economy. Nor do the critics of protectionism mention the huge trade deficit with China. China is in no position to wage "trade war" since the US buys vastly from China than China buys from the US.

Conservatives frequently claim that government regulation is not the answer. The answer, they believe, lies with individual initiative. This maxim has some truth when it comes to jobs and wages. Government regulation alone is not the answer. It is time for workers, especially skilled workers and knowledge workers, to realize that they must organize into associations and unions. By joining together their collective voice will be heard by those who make the laws. The press will be more likely to listen to a professional association than to a single worker. Management may be able to treat an individual badly, but mistreatment is more difficult when management is faced with professionals who stand together.

When professional associations and unions are mentioned for engineers the objectivist line is frequently trotted out: unions do not allow individual talent and initiative to be rewarded. People are promoted on the basis of seniority, rather than skill. Unions like the Teamsters have shown that unions become corrupt and no longer represent the interests of their workers.

There may have been reasons to discard the idea of unions when there was high demand for engineers and most engineers were too young to be concerned with issues like age discrimination and retirement. Those times are past. Unions are not a perfect answer, but we know as engineers that obtaining an objective requires a trade-off. There are rarely perfect solutions. Many of us went into hardware and software engineering because we loved our work. We can either organize or continue to watch the decline of the professions we love.

One group of engineers and scientists that has banded together since the 1970s in an effort to create a better workplace is the Society of Professional Engineers and Scientists, which is associated with the Communication Workers of America.

Web sites that publish articles on wages, globalization and offshoring.

Economic Policy Institute (EPI): Research and Ideas for Working People

The Cato Institute: Individual Liberty, Limited Government, Free Markets and Peace.

The Cato Institute is listed here in an attempt to provide counter arguments to those I have presented here. While I am sympathetic with Cato's stands on the War on Some Drugs and their support for civil liberties, I find many of their writers odious.

Some of these references are repeated from the body of the essay. Most are links to on-line resources. A few are local copies to assure that these references remain available. In general the references are listed in increasing chronological order.

Compiler Development in Bangalore

This is a small web page I've written commenting on a marketing letter sent out by a Bangalore software company, soliciting clients who need compiler development services. Compilers are very complicated software programs and this is an example of how both routine and complex development jobs can move offshore.

Robotic Nation by Marshall Brain

Robotic Nation is an essay on the increasing replacement of jobs by automation. The author (who really is named Marshall Brain) predicts a date (2055) by which he believes that the majority of human jobs in the west will be replaced by robots. Mr. Brain is the author of a the "How Stuff Works" book series and of the How Stuff Works web site.

Mr. Brain points out that the classic response from economists is that workers who are displaced by technology will work in newly created jobs. He has a rather bleak view on this topic:

What will those new jobs be? They won't be in manufacturing -- robots will hold all the manufacturing jobs. They won't be in the service sector (where most new jobs are now) -- robots will work in all the restaurants and retail stores. They won't be in transportation -- robots will be driving everything. They won't be in security (robot police), the military (robot soldiers), entertainment (robotic amusement parks), construction (robotic construction workers), education (robotic teachers and computer-based training), programming or engineering (outsourced to India at one-tenth the cost), farming (robotic agricultural machinery). We are assuming that the economy is going to invent an entirely new category of employment that will absorb half of the working population.

What Mr. Brain does not address in this article is the economics question raised here: if there are no jobs and half the work-force is getting by on government welfare or subsistence labor, there is no market and the economic system will collapse.

Grow Faster Together or Grow Slowly Apart:How Will America Work in the 21st Century? (PDF) by the Aspen Institute Domestic Strategy Group, August 2002

The main thrust of this paper is that there is an impending labor shortage that will become more pronounced as the native born population of the United States ages. The report sites the demographic shift toward an aging population that will (the authors claim), at best, replace those workers who retire or die. Their most dramatic claim is that there will be 0% net increase in the working population.

The report makes the point that there is an increasing wage gap between the educated and those who are not educated. They also point out that people are making less today than they were twenty years ago.

Those of us in software and hardware engineering have heard similar claims for worker shortages. These were loudest during the "dot-com" and telecom bubble in 1999 and 2000. The engineer shortage was used as an excuse to import large numbers of foreign workers who would work for lower wages than experienced engineers. After years of reading "engineer shortage" studies, sponsored by corporations, I am naturally skeptical of the claims made in the Aspen Institute report.

The problems of the wage gap that the authors decry and the instability of current employment would both be helped by a labor shortage. Wages would naturally rise as workers become prized commodities. Productivity increases would come through employing workers in better ways, rather than paying them less. As with the engineering shortage, these "Chicken Little" claims are simply a justification for flooding the US labor market with cheap foreign labor to keep US wages down.

The foundation for software or hardware engineering is a University degree. The technology changes so fast that it requires constant study and mastery of new knowledge and skills. Much of this must be done at night and on weekends. Although engineering is a demanding profession, engineers have been faced with record unemployment. Families have lost their savings and in some cases their homes. Is it any wonder that eduction levels in the United States are declining (as this report claims)? Young people see how hard older professionals work, only to be laid off as corporate executives rake in huge pay packages.

The report's summary is full of empty platitudes and observations of the blazingly obvious. There is no in-depth analysis or suggestions for anything like a real solution. Little else can be expected from a report written by people who are nothing more than corporate shills, funded by the "Fat Cats" of the business world.

The New Global Job Shift by Pete Engardio, Aaron Bernstein and Manjeet Kripalani, Business Week, February 3, 2003

This Business Week article discussions how Bank of America, among others, made huge reductions in their information technology and back office staff by moving the jobs to India. The last paragraph of this article echos the motivation for writing this essay:

The truth is, the rise of the global knowledge industry is so recent that most economists haven't begun to fathom the implications. For developing nations, the big beneficiaries will be those offering the speediest and cheapest telecom links, investor-friendly policies, and ample college grads. In the West, it's far less clear who will be the big winners and losers. But we'll soon find out.

Lets at least start asking the right questions, even if the answers are not obvious.

Toward the Precipice by Robert Brenner, London Review of Books, February 2003

This article is a review of the authors view of economics in the last quarter or so of the twentieth century and the early years of the twenty-first century. Robert Brenner's discussion is echoed in many cases by this essay: when people do not have income, they do not have buying power. Only the rich get rich and the rest of the population struggles.

U.S. tech workers feeling pinch of new world economy by Phyllis Schlafly, June 10, 2003, published on townhall.com, a conservative web site.

Phyllis Schlafly is a long standing and vocal proponent of the "Christian Right". While this essay does not advocate any particular political solution, it does describe in detail the disappearance of "knowledge worker" jobs from the United States to India. The fact that factions of the Republican right wing have taken up this cause, which is also a classic unionist issue, means that the disappearance of US jobs to foreign countries may become a broad spectrum political issue.

Imported From India, CBS News/60 Minutes, June 22, 2003

This is an article on the Indian Institutes of Technology (IIT), in India. IIT has a very good reputation for producing engineers. This article includes various elitist comments by Vinod Khosla, one of the founders of Sun Microsystems, about how IIT produces uber-mensch of the technology world.

White-collar sweatshops: "Globalization" is becoming a dirty word to U.S. tech workers, increasingly angry and anxious as their jobs disappear overseas, never to return, by Katharine Mieszkowski, Salon, July 2, 2003

Tech jobs leave U.S. for India, Russia: Job exports may imperil U.S. programmers, Associated Press, Monday, July 14, 2003, reprinted on CNN.com

Laid-Off Factory Workers Find Jobs are Drying Up for Good by Clare Ansberry, The Wall Street Journal, July 21, 2003, Pg. A1

IBM explores shift of white-collar jobs overseas, By Steven Greenhouse, The New York Times, July 21, 2003.

With American corporations under increasing pressure to cut costs and build global supply networks, two senior IBM officials told their corporate colleagues around the world in a recorded conference call that IBM needed to accelerate its efforts to move white-collar, often high-paying, jobs overseas even though that might create a backlash among politicians and its own employees.

Coding: Should it stay or should it go? By Ed Frauenheim, CNET News.com, July 22, 2003

In this article Greg Owens, a CEO of a small software company Manugistics, is quoted as stating that engineering is still a great profession (while he fires his US workforce and moves their jobs overseas):

At software company Manugistics, for example, the use of about 100 developers in India has corresponded with a cut in the number of U.S. developers from roughly 450 to about 275, CEO Greg Owens told the conference audience. Owens said more cuts are planned for the U.S. work force. Owens' advice to U.S. tech workers is to improve skills, such as learning the latest technology. "I still think it's a good profession," he said.

Small companies have often been cited as the "engines" of job creation. It is interesting to note that some of these small companies, like Manugistics, are active in offshore contracting, limiting the number of jobs created in the US.

There is a rather disturbing business model which may be active here: Hire US engineers who will work hard to make the company successful. Once the company reaches a level where it has sufficient cash flow, ship the jobs overseas and fire the US engineers.

Globalization takes toll on techies, by Martin Wolk, MSNBC, July 24, 2003

The Wal-Mart Way Becomes Topic A in Business School by Constance L. Hays, The New York Times, July 27, 2003

About a year ago, James E. Hoopes, a professor of history and business ethics at Babson College in Massachusetts, began looking at what he called the symbolic aspects of Wal-Mart.

The company's approach to commerce contravenes the American dream for some people, he said. "It's a new kind of twist because it does affect the lifestyles of so many of us," he said. "Its an enormous employer, and it is identified with what's happened with America in the last 25 years." Gone are many of the high-paying skilled jobs that the automotive plants once provided; instead, people are punching a cash register at Wal-Mart for half the money, he added.

That perception of reduced opportunity carries over into spending, he says. "People have a sense of bing trapped in this marketplace," he said. "You work for these low-wage jobs, and you can have your American dream as long as you buy it at Wal-Mart. So the dream is getting standardized, and downscaled, in a way that hasn't happened before."

Gartner Says Tech Jobs Will Continue to Move Overseas by Michael Pastore, Internetnews.com, July 29, 2003

High Tech Worker Visas Come Under Fire By Roy Mark, Internetnews.com, July 30, 2003

This article discusses L-1B visas, which until recently have been little known. These visa were created to allow multinational corporations to transfer overseas employees to the United States. There has been a huge rise in L-1B visa applications as they have been used by "body shops" to transfer low paid workers to the US for contract work. Unlike the H-1B visa there are no regulations that require a company to at least make a pretense to paying a prevailing wage.

Offshore Lore: Myths and facts of white-collar out-sourcing by Jeff Taylor, Reason On-line, July 30, 2003

This brief article claims that the problem of moving software jobs off-shore is not as bad as some claim. Off-shore talent, the author claims, is not as good as US talent and "off-shoring" is must another management fad. Apparently Reason magazine's bias is toward "free markets". So they might be expected to argue against regulations that might work against allowing companies to move US jobs to other countries.

Jobs Go Global Tech jobs are moving overseas at an alarming rate. Other fields may soon follow. Why is it happening? By Laura Fording, August 3, 2003, Newsweek online/SNUBS

The issue of knowledge working jobs moving offshore is a heated one, with workers on one side and companies on the other. This article is an interview with Ron Hira, who is a post-doctoral fellow at Columbia University's Center for Science, Policy and Outcomes and soon to be a professor at Rochester Institute of Technology. As an academic, Dr. Hira has a more objective view and has some interesting observations.

Body Count: Why Moving to India Won't Really Help IT by Robert X. Cringely, August 7, 2003

Some quotes from the article:

There was a story in the news a couple weeks ago about how IBM was planning to move thousands -- perhaps tens of thousands -- of technical positions to India. This isn't just IBM, though. Nearly every big company that is in the IT outsourcing or software development business is doing or getting ready to do the same thing. They call this "offshoring," and its goal is to save a lot of money for the companies involved because India is a very cheap place to do business. And it will accomplish that objective for awhile. In the long run, though, IT is going to have the same problems in India that it has here. The only real result of all this job-shifting will be tens of thousands of older engineers in the U.S. who will find themselves working at Home Depot. You see, "offshoring" is another word for age discrimination.

and...

If a U.S. employer said out loud, "Gosh, we have a lot of 50-something engineers who are going to kill us with their retirement benefits so we'd better get rid of a few thousand," they would be violating a long list of labor and civil rights laws. But if they say, "Our cost of doing business in the U.S. is too high, so we'll be moving a few thousand jobs to India," that's just fine -- even though it means exactly the same thing.

Men at Overwork: The good news is we're more productive. The bad news? They don't need as many of us by Brad Stone NEWSWEEK, August 11 2003

LABOR MARKET LEFT BEHIND: Evidence shows that post-recession economy has not turned into a recovery for workers (PDF), by Jared Bernstein and Lawrence Mishel, August 27, 2003

Although the recent recession was officially declared over as of November 2001, on Labor Day 2003 the job market remains decidedly weak. Unemployment is high and, instead of coming down in the nascent recovery, it has climbed from 5.6% at the recession.s end to 6.2% in July 2003 (the most recent data available). Tracking the nation.s payrolls reveals the worst hiring slump since the Great Depression. And the weak labor market is not just a problem for those without jobs.wages have been growing more slowly for most workers and even falling in real terms for some.

CIO Magazine, September 1, 2003: articles on offshore outsourcing.

CIO Magazine ran an excellent set of articles on many of the issues involved in offshore outsourcing.

The Radicalization of Mike Emmons by Ben Worthen, September 1, 2003

This article is about Mike Emmons, a previously apolitical software engineer who has seen his job moved offshore.

No Americans Need Apply by Ben Worthen, CIO Magazine, September 1, 2003

This article recounts the problems that the software engineer Daniel Soong has had with his job being repeatedly "outsourced" to India.

There has been a lot of ink spilled in the press about how a decreasing number of students in the United States are taking math and science. These articles make the point that the students who take math and science are the technological future of the United States. In many ways Daniel Soong was an ideal student, the sort of student that these articles claim that the US needs more of. Daniel had a passion for programming since he was a kid, programming a Timex Sinclair. He took calculus in High School and graduated with a computer science degree in 1995. Daniel's reward for years of hard work and study is being unemployed since January of 2002 when his last job was moved off shore.

The surface view of knowledge workers like software engineers is that they are like textile workers. What this view ignores is that these are workers who have made an investment on which they expect a return. This investment is real money, in college tuition and the hard work required to get a computer science degree. The investment continues after graduation, as all engineers are required to continually stay abreast of a rapidly changing field. Daniel Soong could not be blamed for feeling that his investment has not paid off. His post college career has consisted of seven years, ending in unemployment. How many students are going to invest in technology when they can at best look forward to an unstable and short career, ending in wages that high school graduates can command?

Especially after September 11, 2001 many corporate executives are willing to spout the line about the patriotism and commitment to the United States. But their actions tell another story. The greed and concentration on short term profits of large multinational corporations is hollowing out the technology infrastructure of the United States. Although these companies were born in the United States and have succeeded because of the United States, they have no allegiance or concern for the long term welfare of this country.

Backlash - Offshore Outsourcing by Christopher Koch, CIO Magazine, September 1, 2003

The fact that large corporations are currently involved in hollowing out the culture which has nurtured them is not entirely lost on these corporations. They fear that there will be a political backlash, resulting in a boycott of their products and services because of their behavior. There is already a move to ban companies that outsource US Information Technology jobs from state and federal government contracts.

The Hidden Costs of Offshore Outsourcing by Setphanie Overby, CIO Magazine, September 1, 2003